Former Presidents Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma won’t be able to hide forever, says the writer.

Image: Independent Media

Whether or not they succeed in their applications to force former Constitutional Court Judge Sisi Khampepe to step down as Chairperson of the inquiry into the State’s non-prosecution of cases recommended for further investigation by the TRC, former Presidents Mbeki and Zuma won’t be able to hide forever.

They must account for the fact that, whether by commission or omission, the work of South Africa’s flagship mechanism to deal with the divisions of the past was effectively shut down under their watch. They must account to the families of victims who laid down their lives for the democracy over which they held sway as President.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission had several distinct functions, including creating public platforms for the stories of victims of human rights violations to be told, making recommendations to the government on rehabilitating a divided and unequal nation, and providing reparations. But its most important legislative role was the granting of amnesty to qualifying individuals.

In their wisdom, the negotiators of South Africa’s democracy might have chosen to place selected apartheid leaders and their minions on trial, like the Nuremberg Trials after World War 2. Or they could have chosen the route of a general amnesty. Instead, they chose a more complex mechanism of partial accountability with a view to contributing to nation-building by establishing a simple truth.

The Chair of the Commission, the late Archbishop Desmond Tutu, described the offer of amnesty to perpetrators of human rights violations as a “carrot” to encourage them to confess their dastardly deeds. For those who elected to take their chances and ignore the amnesty process, or whose amnesty applications were not considered sufficiently truthful or committed to a political goal, there was also a stick. The TRC’s Amnesty Committee was not made up of theologians, but of judges – including Judge Khampepe.

The trouble that’s arisen is that the commission did not have control over the stick; it made recommendations but depended on the integrity of the National Prosecuting Authority to wield it. By not doing this work, the State effectively chose the unconstitutional route of a general amnesty, while rendering the TRC a confessional of no consequences and besmirching its actual purpose.

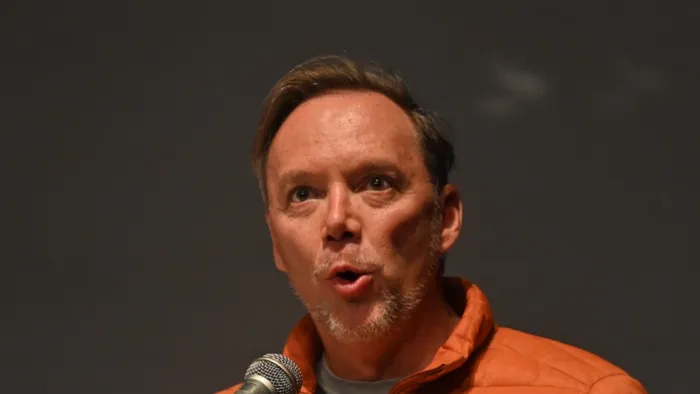

Unite for Change Leadership Council member and GOOD member of the Western Cape Provincial Parliament, Brett Herron.

Image: Ayanda Ndamane/Independent Newspapers

The TRC recommended approximately 300 cases for further scrutiny. Nearly 25 years later, a large proportion of perpetrators have passed away from old age without being held to account, and without offering any sense of closure to surviving family members.

These weren’t just any cases, and nor were they cases of unknown soldiers.

Many of the cases involved the killing of activists, soldiers, and leaders of the ANC. Among the delayed cases was that of the killing of former ANC President and Africa’s first Nobel Laureate, Albert Luthuli.

The inquest was reopened late last year…

Whether former Presidents Mbeki and Zuma, who collectively led South Africa for 18 years, are guilty of actively stopping the further investigation of these cases or simply sitting back and allowing the NPA to grievously wound the national reconciliation project off its own bat- is for Judge Khampepe to decide.

Perhaps the former Presidents will succeed in their legal efforts to force the judge’s recusal and further delay the administration of justice. Either way, if they continue to avoid explaining the truth of these matters, South Africans will form their own opinions. If the former Presidents don’t counter the FW De Klerk Foundation’s version that there was a secret deal on non-prosecutions between the ANC and De Klerk’s NP, many will regard it as the truth.

Abbreviated Timeline:

2003: The last volumes of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Final Report were handed to the government. The Final Report makes recommendations on further criminal investigations (virtually unimplemented), reparations (partially implemented), and societal healing such as a Wealth Tax to narrow inequality (not implemented).

2008: The Ginwala Commission investigating Advocate Vusi Pikoli’s fitness to hold the office of National Director of Public Prosecutions, found that the State had “not made out a case” that Pikoli’s handling of TRC cases rendered him unfit for office. Ginwala was not moved by the argument of the DG in the Presidency that political cases needed broader ventilation than the criminal justice system would afford them.

2008: Pikoli deposed an affidavit in the case of Nkadimeng and Others vs NDPP, alleging political pressure to drop TRC cases. Pikoli repeated these allegations in a second affidavit (in the same matter) in 2015.

2017: Family of anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Timol, who was killed in detention in Johannesburg in 1971, pressures the NPA to reopen the 1972 inquest that found Timol committed suicide.

The murder finding of the reopened inquest adds to pressure on the government being exerted by other victims’ families. Since the Timol case, the State has reopened several other inquests, including that into the death of Chief Albert Luthuli. The State also sought to try the surviving policeman in the Timol matter. Joao Roderigues for murder. Roderigues died of old age while his lawyers sought technical reasons to delay the trial.

2025: In January, families of apartheid victims led by the son of Fort Calata, Lukhanyo, launch damages litigation against the State for failure to prosecute apartheid era killers.

2025: In May, President Cyril Ramaphosa appoints Judge Khampepe to head the Commission of Inquiry.