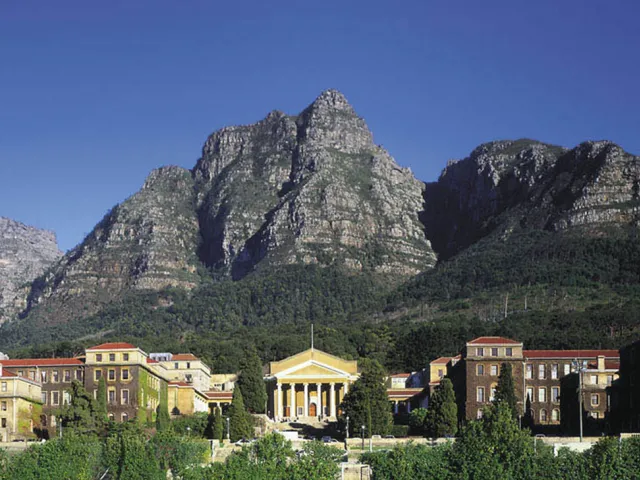

The University of Cape Town.

Image: Supplied.

At the beginning of November , the University of Cape Town formally announced that final academic results would be released on December 19 at 14:00.

For thousands of students, this date marked the end of an exhausting academic year one shaped by financial stress, uncertainty, and survival. Results day is supposed to be a moment of truth: a moment when students finally know where they stand.

But when December 19 arrived, something deeply troubling unfolded.

Results were released earlier than the stated time yet only a specific group of students could access them. These were students whose fees were fully paid, students from financially secure backgrounds. In the South African context, and particularly at UCT, this group remains overwhelmingly white.

For the rest students who are financially indebted the system was completely closed. No marks. No course history. No academic visibility at all.

This was not always the case.

What Changed: from administrative restriction to total academic blackout

Historically, UCT has maintained a clear distinction between official academic documentation and basic access to results. Students with outstanding fees were denied official transcripts, but they were still able to view their marks through the Class Management tab or Course History on PeopleSoft. This practice, while still problematic, at least recognized a basic academic right: the right to know how one performed.

That limited access mattered. Even when students were financially blocked, they could still see which modules they had passed or failed, how they had performed in each course, and whether they qualified for progression. This information was crucial for students who were academically excluded, as exclusion letters are issued without detailed marks. Without access to results, students are left unable to see which modules they failed, how close they were to passing, or where their academic weaknesses lay.

Previously, being able to view marks allowed students to prepare accurate and evidence-based appeals, grounded in their actual performance across courses. Academic knowledge, while constrained, was not yet fully weaponised

This year, however, that distinction collapsed.

UCT deliberately closed every alternative access point. Students who owe fees cannot see anything not a single mark, not a single course outcome. Academic performance has been placed behind a financial wall.

This is not a minor technical adjustment. It is a fundamental shift in institutional posture.

Debt at UCT is racialised debt

The university may frame this issue as one of “fees” or “debt,” but in South Africa, debt is never racially neutral.

Students who owe fees at UCT are not an abstract group. They are predominantly Black students, funded by NSFAS, students affected by funding shortfalls, delayed payments, accommodation costs that exceed allowances, and unfunded students from working- and lower-middle-class households.

NSFAS exists precisely because apartheid systematically excluded Black people from economic participation. It funds students who come from poor and working-class backgrounds that remain overwhelmingly Black due to historical and structural inequality. When NSFAS fails to cover the full cost of study, the debt does not disappear; it is transferred onto the student.

As a result, the category “student who owes fees” at UCT is, in practice, a Black category.

By contrast, students who can easily settle fees often upfront tend to come from financially stable families. At UCT, this group still reflects the racial legacy of privilege: largely white, or at least economically insulated.

So, when results were released on December 19, two realities emerged side by side:

- Students from “proper” or financially secure families logged in and immediately saw their results.

- Black students, many of whom have worked just as hard or harder were met with blank screens and blocked access.

One group entered the festive season with certainty. The other entered it with anxiety, silence, and exclusion.

Financial policy as a tool of discipline

UCT has previously acknowledged that restricting access to results increases payment compliance and reduces institutional debt. This admission is crucial. It reveals that blocking results is not an unfortunate by-product of financial management it is a strategy.

In this context, withholding results functions as a disciplinary mechanism. It places pressure on students to find money they do not have, often from families already under severe economic strain. The message is clear: pay first, then you may know.

But when such pressure is applied in a society marked by racialised poverty, it does not operate evenly. It punishes Black students for structural conditions they did not create.

This is how contemporary institutional racism works. It does not announce itself openly. It hides behind neutral language “policy,” “systems,” “financial sustainability” while producing predictably unequal outcomes.

The violence of not knowing

The denial of results is not a symbolic inconvenience. It has real, material consequences.

Students who cannot see their results cannot:

- Plan academic appeals

- Apply for funding with accurate information

- Prepare for re-registration

- Make informed decisions about their academic futures

- Even explain to their families how they performed

Uncertainty becomes a form of punishment.

And when this uncertainty is disproportionately imposed on Black students, it reproduces a familiar historical pattern: Black people are expected to wait, to endure, to remain in limbo while institutions pause, close, and “enter the festive season.”

UCT’s transformation question

UCT often speaks the language of transformation, equity, and redress. Yet moments like this expose a deeper contradiction. An institution cannot meaningfully claim transformation while implementing policies that so clearly track lines of race and class.

When access to academic results depends on wealth, education ceases to be a right and becomes a commodity. And like all commodities in South Africa, it is distributed along racial lines.

The events of December 19 are not an isolated administrative issue. They are a mirror reflecting unresolved inequalities at the heart of the university.

Results should measure academic performance not financial position. Until UCT confronts the racial and class consequences of its financial policies, its commitment to justice remains rhetorical, not real.

* Hlamulo Khorommbi is former SRC president

Related Topics: