State of the nation: social cohesion remains elusive in a divided country

YEAR IN REVIEW

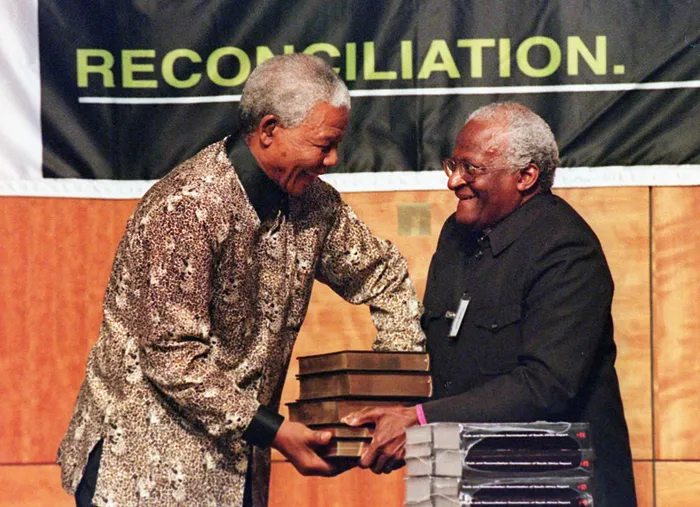

President Nelson Mandela receives five volumes of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) final report from Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in Pretoria on October 29, 1998. South Africa’s unresolved racial tensions, on campuses, on farms, in public discourse, reveal a nation still wrestling with historical accountability and future responsibility, says the writer.

Image: AFP

Dr. Clyde N.S. Ramalaine

South Africa’s social fabric is frayed, and we cannot cloak that truth in euphemism. The 2024 Social Cohesion Index, measuring interpersonal trust, institutional confidence, attitudes to diversity, civic participation, and respect for social rules, offers a picture that is at once sobering and insistently instructive: small gains in isolated pockets, yet large failures in the structural core.

While the index registers modest improvements in neighbourhood solidarity and interpersonal trust, its deeper pillars, confidence in institutions, acceptance of diversity, and adherence to shared norms, continue to deteriorate.

This is not a statistical quibble; it is the slow unravelling of the civic glue at a moment when the country most needs the adhesive of mutual obligation and shared purpose. Coming out of the unstable post-2024 coalition landscape, with governance fractured and political accountability diffused, South Africa enters 2025 with social cohesion not merely weakened but actively endangered.

To be blunt: our crisis is not simply strained relations between neighbours. It is a political economy that manufactures scarcity, cruelty, and competition as default modes of survival.

Beyond the index, the broader research landscape, from HSRC’s longitudinal SASAS studies to fieldwork in rural towns and urban peripheries, reiterates the same truth: poverty, unemployment, broken service delivery, and acute feelings of abandonment by the state are the principal drivers of social disaffection.

When the state cannot provide dignity through work, predictable services, and procedural justice, the informal order that emerges is often exclusionary, predatory, and violent. It is within this furnace of scarcity and inequality that mistrust is forged.

A second layer of the malaise sits squarely in the political sphere. Too often, political actors convert the authority of public office into a platform for rent extraction rather than a public good. Corruption, misgovernance, and institutional decay are not abstract sins; they are moral toxins that erode the habits of reciprocity on which cohesion depends.

Citizens invest trust when they see reciprocal stewardship. Endless commissions, weak accountability, and scandal fatigue drain the moral energy of the republic. Academic calls for a transparent “social cohesion barometer” are not bureaucratic indulgence; they are essential tools for diagnosing where trust has become toxic and where it may yet be rebuilt.

Racial and identity narratives remain among the most potent vectors of fragmentation. The democratic dispensation did not dissolve racialised competition; it merely masked it beneath a less interrogated rainbowist rhetoric. Access to jobs, schooling, safe neighbourhoods, and functioning services still tracks the racial hierarchies of old.

The slogan “Africa for Africans,” once a rallying cry against apartheid dispossession, is now weaponised in what some see as xenophobic campaigns that pit the poor against the vulnerable. Research on opinion leaders and local conflict confirms that inflammatory discourse, amplified by populist elites and unregulated digital platforms, can rapidly escalate instability.

Education and civil society, meanwhile, are both casualties of fragmentation and reservoirs of resilience. Research is unequivocal: teachers, schools, faith communities, and community programmes remain critical mediators of social cohesion. They shape early attitudes toward diversity, justice, and democratic participation.

Yet these institutions are weakened by under-resourced classrooms, outdated curricula, and insufficient teacher preparation for social-justice pedagogy. Where civic formation is embedded meaningfully in schooling, communities show measurable gains in tolerance and participation. But when education is reduced to credentialism, the next generation inherits not a shared nation but a brittle polity. A society that cultivates cognitive skill but neglects moral citizenship will reap the whirlwind of alienation.

Moreover, as we turn from education to the wider environment, a rising stressor emerges that is too often overlooked in public debate: climate change and environmental instability.South Africans have witnessed this firsthand: the KwaZulu-Natal floods, recurrent droughts in the Eastern Cape, and heat shocks that destabilise Limpopo’s agricultural belt.

Climate shocks not only destroy infrastructure; they erode the moral economy of reciprocity. When harvests fail and livelihoods collapse, neighbourliness and communal responsibility come under strain. As climate volatility accelerates, cohesion will be tested less by speeches and more by a community’s capacity to absorb adversity without descending into conflict. Climate adaptation is therefore not only an ecological or economic necessity; it is a social cohesion imperative.

Factors Undermining Cohesion

South Africa’s cohesion is further destabilised by entrenched structural legacies, apartheid spatial design, racialised access to opportunity, and staggering inequality. Despite post-1994 aspirations, the daily realities of life remain profoundly unequal.

High unemployment, intense youth frustration, and widening income gaps foster resentment between communities. Service-delivery failures repeatedly trigger protest cycles, deepening disillusionment with the state. These are not aberrations; they are predictable outcomes of a political economy that has not meaningfully disrupted apartheid’s architecture.

Governance failures compound this burden. Corruption, erratic policing, and uneven application of justice break the basic architecture of trust. Communities competing over scarce water, housing, electricity, and healthcare often turn against one another—a process exacerbated by political actors who manipulate scarcity for factional gain. When competent, equitable governance collapses, citizens retreat into enclaves of identity, locality, or desperation.

Race, Ethnicity, and Cultural Anxiety

South Africa’s unresolved racial tensions, on campuses, on farms, in public discourse, reveal a nation still wrestling with historical accountability and future responsibility. Black South Africans continue to face structural exclusion. Many white South Africans feel anxious or alienated. Coloured and Indian South Africans often feel invisible or misrepresented.

These parallel grievances create a cycle of suspicion and incomplete recognition. Ethnic tensions, whether between African groups or around marginalised KhoeSan identities, remain largely unspoken but politically potent. Instead of cultivating pluralism, the state often imposes homogenised identity narratives that suppress complexity.

Forms of contention, at times too quickly explained as xenophobia, expose the fragility of local solidarities. When economic pressures intensify, the “stranger” becomes an easy scapegoat. Identity politics is not rhetorical theatre; it is a governance arena requiring nuance, humility, and justice.

Economic Precarity and Class Fragmentation

Economic precarity is perhaps the most explosive stressor. Poverty is entrenched and intergenerational. Millions remain in survivalist labour or joblessness. The middle class, one salary away from crisis, is gripped not by solidarity but by fear.

Meanwhile, an elite compact comprising old white capital and new politically connected black beneficiaries remains insulated from public suffering. Cohesion cannot flourish in a country bifurcated between gated enclaves protected by private security and communities surviving amid failing infrastructure.

The Politics and Politricks of Cohesion Narratives

The state’s use of “social cohesion” is rarely innocent. Too often, it becomes a rhetorical shield deployed to maintain legitimacy amid governance failures. Instead of addressing material inequalities, leaders invoke cohesion as a moral admonition while ignoring the structural conditions that fragment society.

Cohesion becomes a political commodity, invoked at conferences, diluted in policy, and abandoned when electoral calculus demands racial, ethnic, or nationalist fearmongering.

Even more insidious is how cohesion rhetoric is used to delegitimise dissent. Communities demanding services are framed as divisive. Workers striking for fair wages are accused of undermining unity. Activists are cast as agents of disorder.

At the corporate level, cohesion programmes become branding exercises masking uninterrupted extraction. CSI initiatives and “nation-building dialogues” too often substitute for substantive transformation in land, capital, or ownership patterns.

Reclaiming the Possibility of Unity

If the diagnosis is grim, the remedies are refreshingly clear: rebuild institutions, restore ethics, democratise prosperity. Trust follows performance; people believe when water flows, clinics function, safety is felt, and justice is delivered.

Accountability must cease to be a formality. Corruption must have consequences. Economic redistribution, job creation, land reform, and access to markets remain the backbone of any meaningful cohesion agenda.

Yet policy alone is insufficient. Leadership must embody the virtues that one of South Africa’s conveniently erased leaders, Sobukwe, lived: self-subjugation, integrity, courage, and consuming love for the people.

Civil society, churches, unions, and community organisations must be resourced not as emergency responders but as mediators of social repair. Practical interventions exist: participatory budgeting, transparent procurement, social-wage job creation, and restorative community forums. Measurement tools must be public-facing; without oversight, measurement becomes an academic ritual.

Finally, the national narrative must shift. We must tell the truth about injustice without surrendering to cynicism. We must craft a story of dignity as shared inheritance, not a privilege of the few.

South Africa stands at a decisive crossroads. The Social Cohesion Index, and the scholarship surrounding it, offers both a map of decline and a compass for renewal. The choice before us is not a technical one; it is a moral one.

Will we rebuild this nation through shared responsibility and ethical leadership, or will fragmentation write the final chapter of an unfinished liberation?

The answer requires courage. The courage Sobukwe insisted on. The courage to refuse corruption, to place the people above privilege, and to imagine a nation where cohesion is no longer aspirational rhetoric but lived reality.

* Dr Clyde N.S. Ramalaine is a Political Analyst, Theologian, and Commentator on Politics, Governance, Social & Economic Justice, Theology, and International Affairs

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.