Implant helps SA teen return to earth

File photo: Surgeons used an outline of his mother Louise's ears as a template, before grafting them on to Kieran's head under pockets of skin. File photo: Surgeons used an outline of his mother Louise's ears as a template, before grafting them on to Kieran's head under pockets of skin.

Bloemfontein - An 18-year-old deaf Thaba Nchu boy was living on another planet before receiving his cochlear implant, he said on Thursday of his life before receiving the device.

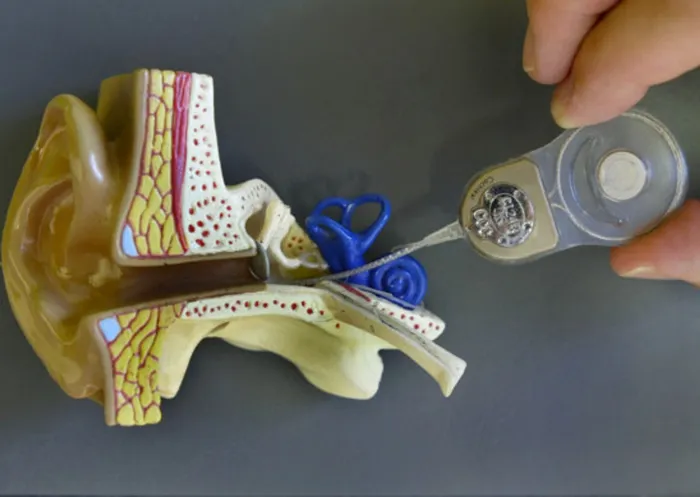

A speech therapist switched on Andile Jantjies' cochlear implant at the department of otorhinolaryngology at the University of the Free State (UFS) moments before his comment.

Ear, throat and nose specialist Dr Iain Butler said the implant would hopefully help him to return to a normal life at school.

“I am grateful and very happy,” said Jantjies, who could again hear for the first time in almost six months.

Jantjies lost his hearing after contracting bacterial meningitis in June 2013.

Butler said this resulted in bilateral profound deafness and despite his good academic record his school refused him enrolment for 2014.

Jantjies received treatment under the Bloemfontein cochlear implant programme run by the UFS department.

The boy's first acknowledgement of hearing a soft beep, led to smiles all around in a speech therapist’s tiny workroom at Universitas Hospital.

His aunt, Gloria Lekoala, could hardly contain her excitement. She pointed to the frown on his forehead as he began to identify the sounds.

“I am happy for him, for he can now go to school,” said a smiling Lekoala.

“He has lost a year, so I am very happy.”

When Jantjies eventually managed to repeat a question from his aunt, Lekoala almost jumped out of her chair smiling.

Recognising and repeating several sounds made by the therapist also brought a nervous smile to the boy’s face.

Butler said Jantjies' case was handled as a medical emergency due to the fact that meningitis causes a build-up of bone in the inner ear.

“This can occur as little as four months after the infection and means that the insertion of a cochlear implant could become impossible.”

Butler said the diagnosis of deafness in children under four, and in meningitis patients, remained a big problem in the health system.

The younger the age at which children were diagnosed and tested for deafness the better. The window of opportunity to help patients such as Jantjies was small.

Butler said there were eight teams doing cochlear implants in South Africa, including the UFS programme. An estimated 45 implants were done a year at a cost of about R220 000 each.

Money remained the biggest hurdle in restoring hearing with cochlear implants, said Butler.

“Parents must go and find money elsewhere for their children to hear, as no medical scheme pays fully for the procedure.”

Butler said the implant would enable Andile to be an economically active individual later in life instead of depending on others.

Jantjies said he was eager to take on schooling again and “pressure” himself with school work. - Sapa