Explore South Africa's heritage: books that keep the nation's story alive

In “Don’t Upset ooMalume!”, Hombakazi Nqandeka offers a guide to Xhosa heritage for those reconnecting with rural homesteads.

Image: Supplied

September is Heritage Month in South Africa, a time to reflect on the traditions, languages and stories that shape the nation’s identity.

While celebrations often highlight music, food, dance and clothing, books remain one of the strongest mediums for exploring heritage.

Literature gives readers a deeper understanding of history, struggle and possibility.

Books preserve oral traditions, document resistance and imagine futures.

They connect generations to the pain of the past and the hope of the present. Classics remind us where we have been, while new works reveal where we are going.

Below are books that capture different aspects of South African heritage and deserve attention this month.

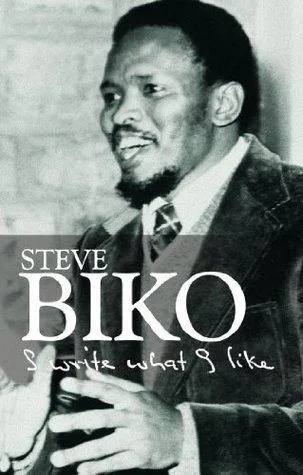

“I Write What I Like” is a powerful collection of essays that shaped the philosophy of Black Consciousness and continues to inspire reflections on identity, resistance and liberation.

Image: Supplied

“I Write What I Like” by Steve Biko

Steve Biko’s collection of essays is central to the philosophy of Black Consciousness.

Written in the 1970s, the pieces challenge systems of oppression and emphasise the importance of African identity and pride.

Biko’s voice continues to resonate more than four decades after his death. His words call for dignity, justice and the reclamation of culture, making the book a vital read this month.

Combining personal observation, testimony and poetry, "Country of My Skull" captures the emotional and political weight of truth-telling after apartheid.

Image: Supplied

“Country of My Skull” by Antjie Krog

Antjie Krog’s work documents the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, one of the most significant chapters in South African history.

Combining personal observation, testimony and poetry, the book captures the emotional and political weight of truth-telling after apartheid.

Krog examines guilt, forgiveness and memory, showing how reconciliation remains a central part of SA’s story. Reading it during this month reminds us that heritage is not only about celebration but also about reckoning with pain and seeking healing.

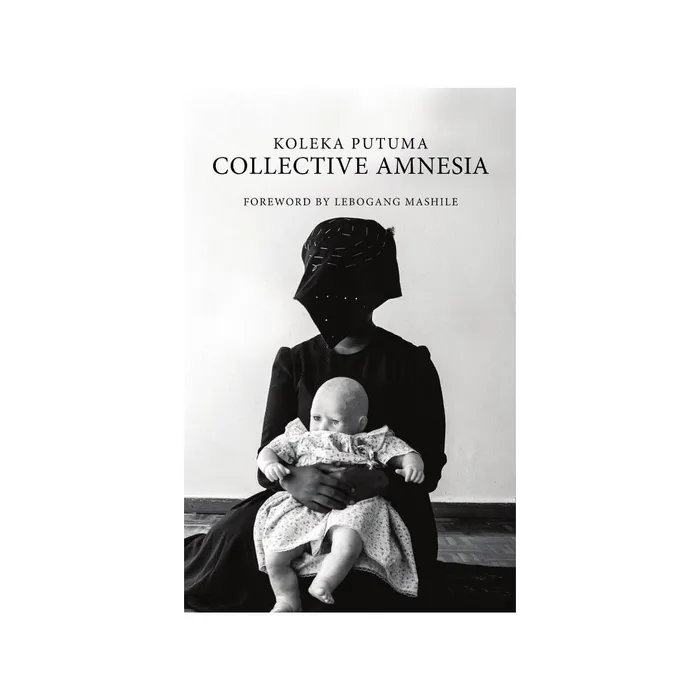

"Collective Amnesia" reflects on how personal experiences intersect with collective history.

Image: Supplied

“Collective Amnesia” by Koleka Putuma

Koleka Putuma’s poetry collection examines blackness, womanhood and history with sharp clarity. Her poems demand visibility and accountability while offering spaces of healing.

Putuma questions authority in religion, politics, academia and relationships. She explores grief, sexuality, memory and self-care, pointing to what must be unlearnt as much as what should be remembered.

The book reflects on how personal experiences intersect with collective history. It challenges silence and insists on truth, positioning poetry as both testimony and resistance. The collection has become one of the most important recent contributions to South African literature.

In “Born to Kwaito”, the authors trace the movement from artists like Alaska and Trompies to the likes of Boom Shaka and Brown Dash.

Image: Supplied

“Born to Kwaito: Reflections on the Kwaito Generation” by Esinako Ndabeni and Sihle Mthembu

Kwaito is one of the defining cultural movements of post-apartheid SA. Emerging in the 1990s, it was more than a music genre. It was an expression of freedom, identity and self-definition for a new generation.

In “Born to Kwaito”, Esinako Ndabeni and Sihle Mthembu trace the movement from artists like Alaska and Trompies to the likes of Boom Shaka and Brown Dash.

Kwaito shaped the sound of townships and the cultural mood of a nation in transition. The book highlights the way Kwaito challenged patriarchy, celebrated everyday life and gave young black

South Africans a soundtrack for their democracy. Figures like Brenda Fassie, Lebo Mathosa, Thembi Seete and Thandiswa Mazwai not only made music but created cultural movements.

By revisiting Kwaito, the book captures a heritage that is recent but deeply influential.

“Khamr: The Makings of a Waterslam” explores Jamil Khan’s experience of growing up with an alcoholic father while navigating a Muslim upbringing that rejected much of what defined his home life.

Image: Supplied

“Khamr: The Makings of a Waterslam" by Jamil F. Khan

“Khamr: The Makings of a Waterslam" is Jamil Khan’s account of growing up in a Coloured household in Bernadino Heights, Kraaifontein, north of Cape Town.

The memoir centres on his experience of living with an alcoholic father while navigating the expectations of a Muslim upbringing that condemned much of what surrounded him at home.

Khan traces his life from childhood into early adulthood, describing the chaos of addiction, the strain of a co-dependent relationship with his mother, and the pressure to maintain academic excellence while his parents worked to keep up appearances.

His recollections are vivid, and he uses them to interrogate broader questions of identity, culture and class.

Through sharp analysis, Khan examines how Islam, Coloured identity and respectability politics intersect with the realities of dysfunction and survival.

Rather than offering only a narrative of hardship, the book reflects on how memory and scholarship can be woven together to understand family, faith and belonging.

It is both personal testimony and social critique, written in a voice that is clear and questioning.

In “Don’t Upset ooMalume!”, Hombakazi Nqandeka offers a guide to Xhosa heritage for those reconnecting with rural homesteads.

Image: Supplied

“Don’t Upset ooMalume!” by Hombakazi Nqandeka

In “Don’t Upset ooMalume!”, Hombakazi Nqandeka, writer and agriculturalist, provides a guide to Xhosa heritage for those returning to rural homesteads.

Drawing from her childhood and lessons passed down by her grandmother and mother, she explains customs ranging from greetings and ceremonies to clothing, food and rondavel life.

The book also introduces traditional plants, their medicinal uses and recipes, while highlighting the role of nature and animals in Xhosa culture.

Nqandeka’s concern that this knowledge might be lost to younger generations drives the work. She aims to reconnect readers with their roots and ensure that cultural practices remain alive for years to come.

Related Topics: