The future of akoya pearls: Climate change and an aging workforce threaten Japan's pearl industry

A worker at the Union Pearl factory in Ise, Japan, sorts through cultivated pearls.

Image: Salwan Georges/The Washington Post

For generations, the lustrous akoya pearls, reminiscent of the classic styles worn by fashion icons such as Audrey Hepburn and Jacqueline Kennedy, have epitomised understated elegance and timeless allure. These perfectly round, white pearls, sought after globally, hail from the serene waters of Ago Bay in Japan, where conditions have long been ideal for oyster cultivation. However, a double existential crisis now looms over this storied industry: rising sea temperatures are weakening oysters while an aging workforce struggles to find successors for the family-run businesses that have thrived for over 130 years.

“The akoya pearl oysters are delicately nurtured by farmers who utilise techniques passed down through generations,” said Akihiro Takeuchi, a revered third-generation pearl farmer.

Akihiro Takeuchi, a third-generation pearl farmer, tends to his oysters in Ago Bay.

Image: Salwan Georges/The Washington Post

“After being artificially fertilised and incubated, the spat are transferred to the sea, where we monitor their growth closely.” This meticulous process, perfected over decades, requires farmers to regularly check water temperatures to ensure a hospitable environment for the oysters. However, the harsh realities of climate change have disrupted this delicate balance.

Takeuchi's farm faced devastation six years ago when he lost 80 per cent of his juvenile oysters to an unfamiliar illness identified as a novel strain of birnavirus, which had proliferated across Ago Bay's farms. Researchers speculate that the increasing water temperatures, which have risen by 2.4 degrees over the last century, have left young oysters — some no larger than a pinkie nail — particularly vulnerable to this contagious virus. This year, as 2024 brings record sea temperatures, the formidable challenges for pearl farmers have only compounded.

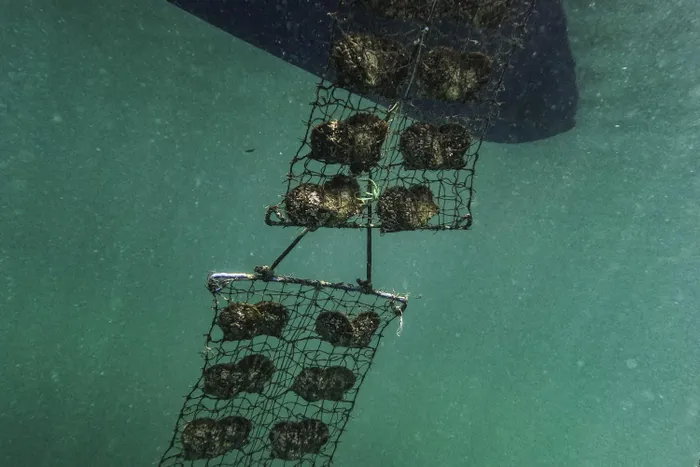

When ready for cultivation, “mother” pearls are transferred to nets on long ropes attached to buoys.

Image: Salwan Georges/The Washington Post

The Japan Meteorological Agency has reported that the average sea surface temperature reached 2.59 degrees Celsius higher than normal, leading to alarm within the pearl farming community. The ramifications of this environmental upheaval have been staggering. In 2023, pearl production plummeted to a mere 13.2 tons, marking the lowest output since records began in 1956. Shockingly, this is a stark contrast to the production peak of 138 tons in 1967. Despite these setbacks, demand for pearls continues to soar, with Japan exporting $290 million worth of pearls last year — its highest figure since 2000.

Much of this demand has come from Chinese buyers in Hong Kong, who represented 81 per cent of last year's exports. As a further testament to the complexities facing farmers, while prices rise on the global market, the actual availability of high-quality akoya pearls dwindles, leaving both farmers and consumers in a precarious situation.

Takeuchi lowers his nets into the sea. It takes about two years for the spat to grow into “mother” oysters, which are ready for pearl cultivation.

Image: Salwan Georges/The Washington Post

Oysters thrive in waters between 68 and 77 degrees Fahrenheit, yet the summer heatwaves have trapped warmer air in Ago Bay, elevating temperatures to a perilous 86 degrees in recent seasons. To mitigate these challenges, pearl farmers are innovating by selectively breeding oysters to develop strains that can resist heat and illness. Additionally, they are relocating farms to deeper, cooler waters and segregating young oysters from older ones to combat the spread of the birnavirus.

The cultivation process itself resembles that of intricate organ transplant surgery. Farmers calm the oysters by storing them together in bins — akin to an anaesthetic — before a nucleus is carefully implanted to stimulate pearl formation. “The oyster’s condition, the precision of the operation, and the environment thereafter are all crucial to creating high-quality pearls,” explains Michiyo, Takeuchi's mother.

Takeuchi, right, and his neighbor, Kenji Yamaguchi, 71, check the water temperature in Ago Bay.

Image: Salwan Georges/The Washington Post

Despite the allure of akoya pearls, which are revered for their mirror-like sheen and unrivalled quality, the industry faces an uncertain future. Over the past three decades, a stunning 77 per cent of pearl farming businesses have vanished, as young generations favour urban careers over the demanding lifestyle of pearl cultivation.

The fate of Ago Bay's pearl industry hinges on innovative solutions to climate-induced challenges and the rallying of younger farmers to invest in their heritage. As this iconic industry confronts its challenges, both the delicate pearl and the legacy of generations hang in the balance.

The iconic akoya pearl industry of Ago Bay is facing a critical moment as climate change and an aging workforce threaten its existence. Discover how these cherished gems might just withstand the mounting challenges of our time.

Related Topics: