Caught in Home Affairs horror because of his Khoi name with an exclamation mark!

Lesle Jansen and !Khūboab Oedasoua Lawrence

Image: Tracy-Lynn Ruiters

A Mother is screaming for help to Home Affairs, who has denied her son an Identity Document, all because of an exclamation mark (!) in his name.

For nearly a year, 18-year-old !Khūboab Oedasoua Lawrence has existed in a bureaucratic limbo recognised by his family, his community and his culture, but not fully by the state.

!Khūboab applied for his identity document in 2024 and received confirmation from the Department of Home Affairs acknowledging receipt of his application on 3 April last year. Almost a year later, the document has still not been issued, with officials citing technical limitations related to the processing of “special characters” in his name.

For his mother, Lesle Jansen, the delay is not merely administrative. She says it strikes at the core of her son’s constitutional rights, human dignity and cultural identity as a Khoikhoi man.

“These responses are causing quite a bit of stress for my son,” Jansen said. “But this is not just about paperwork. This is about his identity and his dignity.”

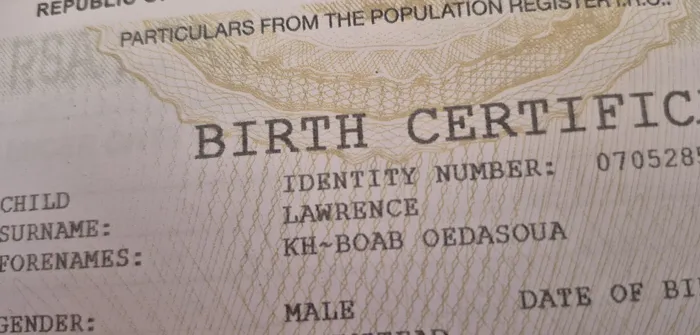

!Khūboab Oedasoua Lawrence operates with a birth certicate and the nae Home Affairs first gave him and is now failing to issue an ID with the same name

Image: Tracy-Lynn Ruiters

While the lack of an identity document has had practical consequences including complications around exams and administrative processes Jansen insists the deeper issue is the continued erasure of indigenous identity within government systems.

“Our family is Khoikhoi. It was important to us to give our son a name in our indigenous Khoekhoegoewab language, one that represents his culture and heritage,” she said.

That decision, however, has resulted in years of struggle.

When !Khūboab was born in 2007, Jansen said the Department of Home Affairs informed her that his name could not be registered in its correct form because the language uses special characters including the click consonant represented by an exclamation mark.

“They told me they would have to remove the special characters,” she said. “Once you remove them, you change the meaning of the name completely.”

His name, she explained, was chosen because it means “man of God”.

“Faced with the legal requirement to register a birth within 30 days, we had no choice,” Jansen said. “We were forced to accept a heavily anglicised and butchered version of his name on his birth certificate.”

Seventeen years later, when applying for his identity document, the family hoped that advancements in technology and constitutional protections would result in a different outcome. To avoid further delays, they submitted the application using the same spelling that appears on his birth certificate without any special characters.

“It unfortunately was not different,” Jansen said. “Now we are being told his ID cannot be printed because of special characters, even though there are no special characters in the name we applied with.”

The prolonged delay has taken an emotional toll on !Khūboab, who says the fight is about more than a document.

“I identify myself as Khoi. I know who I am and I want my identity document to reflect this,” he told the Weekend Argus.

“My name was given to me with a purpose. Like Gabriel, I am !Khūboab ‘man of God’. The chief explained that if even just the exclamation mark is taken away, my name has no meaning,” he said.

“I just want this sorted.”

Jansen said the situation amounts to a violation of her son’s constitutional rights.

“He has the right to have an identity,” she said. “What makes it even more confusing is that the national coat of arms contains special characters and is recognised, yet my son’s name cannot be.”

She questioned how the state expects her son to function as an adult without an identity document.

“He cannot operate with a birth certificate for the rest of his life,” she said. “By 18, a birth certificate is no longer sufficient identification, and the passport he currently uses will expire soon.”

“What do they expect him to do? Apply for a driver’s licence with a birth certificate? Get married with a birth certificate? Register his own children’s births one day with a birth certificate?” she asked.

“This needs to be sorted out. He should live with his birth-given name, and they must solve it. It does not matter how but it needs to be solved.”

Jansen believes the root of the problem lies in the continued marginalisation of Khoekhoegoewab (a Nama language), which is not recognised as an official indigenous language on par with others in South Africa.

“The bigger challenge my son is facing is that Khoekhoegoewab is not recognised,” she said. “Because of this, the Department of Home Affairs does not have the infrastructure to accommodate the characters that are fundamental to the expression of our language.”

She said the situation echoes the historical struggle of Khoikhoi people for recognition and equality.

“The continued delay reminds us of our struggle for recognition that has lasted more than 300 years,” she said. “We are still fighting to be seen and acknowledged for who we are.”

The family has called on the Minister of Home Affairs to intervene urgently and ensure that !Khūboab’s identity document is issued, warning that the failure to do so entrenches inequality and undermines constitutional commitments to dignity, equality and cultural expression.

Chief !Garu Zenzile Khoisan, chairman of the Western Cape First Nations Collective, said the case reflects a broader and deeply troubling pattern within the Department of Home Affairs.

“The obvious hardship that this young person is being put through reflects a general disconnect between the actions of Home Affairs and the people who have to suffer the consequences of an increasingly insensitive bureaucracy,” he said.

“In this instance, where you are dealing with a First Nation descendant, a Khoikhoi descendant, there is an inability to show compassion for the fact that this person is asserting an inalienable right - the right to an identity.”

Khoisan said identity is not symbolic, but foundational.

“To have that identity protected in law and codified through a process where it is legally valid is what opens the pathway to personal development,” he said.

He stressed that !Khūboab’s case was not isolated.

“This is not the only instance where this has happened. I personally know of a young man who is now 26, who applied more than two years ago to change his name at Home Affairs,” Khoisan said.

“He paid all the fees, completed the biometrics and followed every procedure. All he wanted was to be known by his chosen name.”

According to Khoisan, the application was left unattended for more than a year before the applicant was eventually told his request had been denied.

“What happens in that situation is that the person is left in complete limbo,” he said. “Your identity and your name are central to who you are as a human being.”

Khoisan said the matter was eventually escalated to the Public Protector, who ruled that the Department’s Director-General must resolve it a ruling he said has still not been acted upon.

“That ruling was effectively treated as meaningless,” he said. “This shows a department that is recalcitrant and repeatedly in dereliction of its duties.”

He said the broader issue is the lack of recognition afforded to Khoi and San languages.

“The Khoi and San languages are not recognised as official languages in South Africa,” Khoisan said. “Yet on our national coat of arms, right underneath it, is our language.”

“This is part of a broader pattern of othering and making us invisible. It is a disgrace that the language can be recognised on the coat of arms, but when that same language is bestowed in the name of a person, the state cannot act on it.”

Khoisan said the case highlights what he described as a need for systemic reform within the Department.

“There needs to be a serious shift in how officials engage with the people they serve,” he said. “This is about empathy, dignity and respect.”

The Department of Sport, Arts and Culture (DSAC) noted the concerns and encouraged affected parties to engage with relevant service-delivery departments and to lodge complaints with PanSALB or the CRL Rights Commission where linguistic rights are perceived to have been violated.

“South Africa’s Constitution affirms the importance of promoting and protecting all official and indigenous languages as part of preserving the country’s linguistic and cultural diversity.”

The Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB) said the delay in the issuance of an identity document to !Khūboab constitutes a direct violation of his constitutional rights to education, language and cultural identity.

“This matter reflects justice delayed, which in effect amounts to justice denied,” PanSALB said.

The Board said the delay has direct implications for the young man’s ability to fully express and live out his cultural identity, consequences it said could have been avoided.

“Had there been proper consultation with PanSALB by the relevant service-delivery department responsible, this situation could have been prevented,” the Board said.

PanSALB reiterated that state institutions have a constitutional obligation to protect and promote linguistic and cultural rights, particularly for historically marginalised indigenous languages, and called for stronger interdepartmental coordination to prevent similar cases in future.

Thulani Mavuso, spokesperson for the Department of Home Affairs and deputy Director-General: Operations, said South Africa has taken legal, policy and administrative steps to embrace indigenous names in line with constitutional values, human dignity, and international human-rights standards.

"This approach is evolutionary and spans the domains of law, civil registration systems, language policy, and identity restoration. On its part, the Department of Home Affairs has implemented civil registration reforms to ensure inclusive recognition of indigenous identities.

"The National Population Register (NPR) allows for the capture of Indigenous names containing click consonants, diacritics, and non-Anglicised structures; names derived from indigenous languages such as isiZulu, isiXhosa, Setswana and others; and correction or amendment of names that were previously distorted due to colonial or apartheid-era administrative limitations.

"The current legacy system allows for names captured on the NPR to be fully transmitted to the Green Identity Document (Green ID Book), where they are reflected exactly as recorded on the NPR.

He said however, the new live capture system used for Smart ID Card and Passport applications has not yet been fully optimised to accommodate all special characters, including those used in indigenous languages that rely on click consonants and diacritics. As a result, the Smart ID Card application for !Khúboab Oedasoua Lawrence could not be processed to completion, as the name contains two special characters, namely “!” and “ú”, which the current system is not yet able to process.

He said the Department is actively implementing system enhancements to ensure that all names containing special characters are fully accommodated across all civil registration and identity management platforms, in line with constitutional and human-rights obligations.

"In the meantime, !Khúboab Oedasoua Lawrence can visit a non-live capture office to submit an application for a Green ID Book whilst the Ddepartment is working on the implementation of system enhancements."

Related Topics: