Black Wednesday is as relevant now as it was in 1977

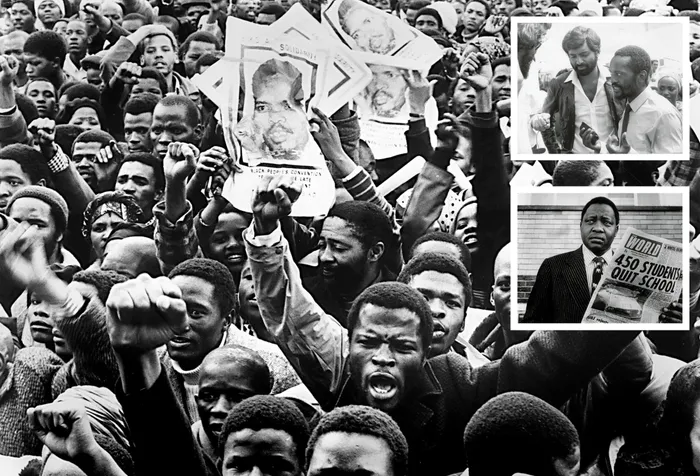

Mourners at the funeral of Black Consciousness (BC) leader Steve Biko in King William’s Town on September 25, 1977. INSET TOP: Then South African Students’ Organisation leaders Saths Cooper, Aubrey Mokoape and Strini Moodley were imprisoned for their BC activism. INSET BELOW: Percy Qoboza, editor of The World and Weekend World. In the aftermath of Biko's murder the apartheid regime banned 19 BC organisations, The World, and The Weekend World, and Qoboza was detained without trial.

Image: Independent Media Archives

On October 19, 1977, the apartheid government launched a brutal attack on opposition groups, individual activists, and the media.

Its particular target was the alternative media – the free press – read primarily by black South Africans. The World newspaper and its sister publication the Weekend World, two anti-apartheid titles, were banned, and editor Percy Qoboza, and his deputy Aggrey Klaatse, were arrested.

This followed the death in police custody of Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko just a month prior on September 12, and it galvanised activism in South Africa.

Black Wednesday was the lowest point in history for the media in South Africa. Direct government censorship, a direct assault on the truth. Controlling the narrative is a key part in maintaining the upper hand in any war, and when truth becomes your enemy, you find yourself on the wrong side of history.

We recognise this dark time in South Africa's history; but we also recognise this in the murder of hundreds of journalists covering the genocide of Palestinians by the Israeli apartheid regime.

South African media's fight for freedom is far from over, however. We face more diffuse threats, and while our lives may not be threatened as regularly as the journalists bravely fighting apartheid, our very existence is under threat.

The enemy was clear in 1977 – the threat was a monolithic, identifiable enemy: the apartheid state. The government used blunt-force tools: banning, arrests, outright censorship. The battle lines were clear.

Today, the threats are multi-pronged, often ambiguous, and diffused. Instead of government censorship, media companies face algorithmic manipulation; the downgrading of prominence on social media sites and search engines, in favour of engagement-rich, sensationalist, and often unverified content flooding timelines and feeds. Hell, you just need to look at the censorship of certain words and the language used on social media.

"He unalived his wife with a pew-pew after graping her."

This manipulation of language is a form of censorship. Serious, mainstream and even alternative media houses wouldn't use this kind of language in their reports, but the language we use – murder, gun, rape – is flagged and the content downgraded.

Happening in tandem is the proliferation of corrosive misinformation and disinformation – sometimes run as campaigns by both state and non-state actors. The sheer volume of content being created every second, worldwide, often makes it easy for incorrect information and outright lies to become the truth, purely through the effects of amplification. There are simply more of them, than there are of us.

Media today also face sophisticated corporate and political lobbying, and we become more vulnerable to this due to economic pressures. You only need to look to the coverage of Israel's Palestinian genocide by the various media houses in South Africa. Independent voices like IOL have been consistently clear on our stance on Israel's aggression, supportive of the South African government's case against the rogue nation at the International Court of Justice, and were the only publications to create a special report on 20,000 children murdered by the IDF.

IOL has been at the forefront of some of the most pivotal breaking news stories that have rocked the nation to its core.

From uncovering the multi-million rand PPE scandal at Tembisa hospital that laid the foundation for the investigation that uncovered billions of rands worth of fraud, to being the first to break the news of the murder of arguably South Africa's biggest music star, AKA, to our continued coverage of Cyril Ramaphosa's Phala Phala home invasion that resulted in the discovery that our Commander-in-Chief had squirrelled away hundreds of thousands of dollars in foreign currency in his furniture. This reportage laid the foundation for the judicial commission of inquiry that found Ramaphosa had a case to answer.

Through our coverage of the Parliamentary ad hoc committee inquest and the Madlanga Commission of Inquiry into police corruption, IOL is lifting the lid and showing South Africans and the world the true state of affairs.

By holding power to account, our reportage results in action and consequences.

We will continue to bring South Africans the news they need to know, the news that helps them make sense of their world around them, and demand accountability from its leaders.

This Black Wednesday, we honour the journalists and activists who died for our freedoms, who gave their lives so the freedom of the press could be enshrined in South Africa's Constitution. We also recognise the hard fought battles waged on multiple fronts to continue to uphold those freedoms and the responsibilities that come along with it.

On October 19, 1977, the apartheid government launched a brutal attack on the media, targeting voices that challenged its narrative. As we reflect on Black Wednesday, we must confront the ongoing threats to press freedom in South Africa and the lessons we can learn from this dark chapter in our history, writes IOL Editor Lance Witten.

Image: IOL

* Lance Witten is the Editor of IOL.

Related Topics: